This article was inspired by Angela Fan’s Talk on Efficient Transformers at AMMI Deep NLP class, 2020. Angela Fan is a PhD candidate with Facebook AI in France.

Here’s what we will cover:

- Introduction

- What we mean by efficiency

- A closer look at standard neural networks

- Techniques for making efficient models

- Conclusion

Introduction

Most research directions in AI are geared towards beating the State-of-the-art on various benchmarks. As such, researchers tend to put in all their compute power and complexity to achieve this goal. This leads to trends of building bigger models with more complex architecture, for a little gain in accuracy. We need to start thinking more in terms of efficiency of the models we build and how it impacts on further research. A model that is very big and complex will loose interest from low-resource researchers and students who want to quickly experiment.

Efficiency in the context of neural networks deal with;

- Faster training time

- Fast inference time

- Smaller model size

- Low energy consumption etc.

For example, with the introduction of the Transformer architecture in the NLP domain, the field has achieved giant strides, pushing up SOTA results i almost all NLP domains. The Transformer has an interesting architecture with parallel computations and self-attention mechanism. A major concern is its parameter size due to the multi-head attention. A recent architecture from Google called Reformer uses locality-sensitive-hashing (LSH) to address this. Similarly, in Computer vision domain, models like ResNext with repeated blocks have shown to have great performance of Image-related tasks, at the expense of speed. These models are difficult to train and experiment with on low-memory GPUs. Therefore, how can we make this models more efficient without loosing performance?

This article was written to give an introductory view on this subject, and hopefully inform Researchers and Machine Learning Engineers like me, on what to have at the back of our minds when we build models and do research.

What we mean by efficiency

Let me expand on the points I made earlier about efficiency. Efficiency is relative and we are talking here in terms of our current memory capacity for on-device AI, mobile applications, computation speed etc.

-

How long will it take to train the model?

One thing I like to scan for in AI research papers these days is the total training time of the model. Many SOTA models take like 1 week to 2 months to train. With that in mind, I know where to focus my reading as it will be difficult to replicate the same results. I entered into a NeurIPS paper implementation challenge last year but got really discouraged by the number of days it will take to verify experiments. I understand that I can track my loss values and accuracy as I train, but the final pre-trained model still takes that long. For example, the Google Meena Chatbot was trained for 30 days using cloud TPU Pods (2,048 TPU cores). 30 days of pre-training is a long-time for experimentation and reproducing results. -

How long will it take to get predictions?

This is really important for models that require streaming predictions. For example, a model that performs auto-correction, or spellcheck must be able to give fast predictions without latency. This is really important for great user experience in AI-powered applications. For instance, Instagram filters must render image filters to users split of seconds to be considered efficient. -

Will the model fit in memory?

This is a really important aspect of efficiency that is being overlooked by the big models. Each year, the model becomes bigger and bigger in size, ensuring that memory sizes are increased to cater for this fact. We need to consider that the amount of memory/RAM available for experimentation on platforms like Google Colab and Kaggle are limited, and I would still like to experiment. I will like to observe that these models usually have a smaller version, but most times, do not perform as well as the large counterparts. As a case study, the OpenAI GPT-2 released in 2019, was so good that the source code wasn’t going to be released at first. It contained 1.5 billion parameters. Wow!! How do I use that on a mobile platform? -

How much energy will it require for training?

Many AI research papers do not track or report the total power used in training their models. I think it will be more useful to have these results for comparism. Neural networks are implemented as computation graphs, and support vectorized implementations with GPUs and TPU support for faster computation. This is great considering the progress in hardware design but most on-device applications still require cpu for computation. Needless to say that, if on-line training will e required by these on-device models, then the computational cost increases as these models might not have been made with this specification in mind. For energy conservation sake, we need models that can perform efficient computations. -

How much energy will it require for inference?

Energy consumption at inference time is another great consideration, especially for on-device AI applications that utilize other power sources like batteries for inference. We would like a model that runs effortlessly without consuming a substantial amount of energy.

This is a requirement for on-device applications, as this improves the experience of users. It makes no sense to run an application for 10 minutes and have to recharge afterwards due to low power.

Our goal should therefore be to retain model performance or perform better, while aiming for more efficient models.

A closer look at standard neural networks

Neural networks as computational graphs show some distinct traits which make them powerful and able to outperform their counterparts on many tasks. The first observation is that they are universal function approximators and are therefore prone to overfitting on any task. This is both a blessing and a bane. Also, modern neural networks are build to be over-parameterized to accommodate for more model capacity. Therefore, regularization is usually required to prevent overfitting.

Increasing layer cardinality is also common in these models e.g ResNet, Inception, BERT etc. This also implies that some of the layers of the network may be redundant and may be learning similar properties. Skip connections and dynamic connections have been used in these large models to cater for this effect and ensure that gradients can be back-propagated efficiently. Similarly, the hyperparameters such as number of filters, number of multihead attentions, size of layers are made bigger than they should be just to squeeze out the performance.

This is better expressed by the Lottery Ticket Hypothesis postulated by MIT researchers.

The Lottery Ticket Hypothesis states that

“A randomly-initialized, dense neural network contains a subnetwork that is initialized such that — when trained in isolation — it can match the test accuracy of the original network after training for at most the same number of iterations.”

What a great discovery!!!

Techniques for making efficient models

-

Train a smaller model from scratch.

This looks obvious at first. If you want a model with smaller size, why not train yours with smaller weight sizes, less number of layers etc. Well, it turns out that this has the advantage of training faster, with smaller model size but with great performance drops. If you consider, most big models, they increase the model sizes to get better performance on the benchmark datasets. Also, intuitively, smaller models have lower capacity and may not be able to learn all the intricacies of the task to perform. As such, these smaller models are only used as proof-of-concept. Can we do better than this? Well, that’s why we are researchers and engineers right? We have to know that any proposed methods of increasing efficiency has to perform better than just this to be so cool. -

Sparsity Inducing Training

The goal of sparsity inducing training is to set as many weights as possible to zero during training. This brings about faster computations especially for on-device AI where we are watchful of number of computations as we have efficient methods - such as the Compressed Sparse Row Format (CSRF) or Yale format and the Compressed Sparse Column Format (CSCF) - for storing sparse matrices. Sparsity can be induced in various forms. For example, through the model loss (as in L1 and L0 regularization), removing small magnitude weights, and some other bayesian methods. For a more concrete review of these methods, check the paper titled “The State of Sparsity in Deep Neural Networks” by Trevor Gale et al. -

Knowledge Distillation

In knowledge distillation, a large, accurate network teaches a smaller network how to behave. That’s cool right? The large network known as the teacher instructs the smaller network called the student. This can be done done via two training methods;

Case a: Student model learns to mimic the output of the teacher model, getting its loss from only the output layer

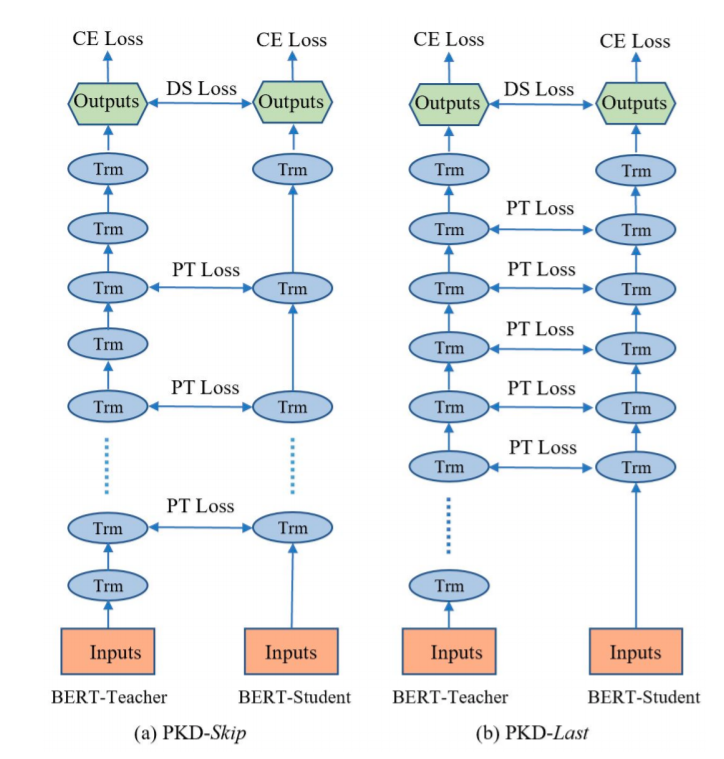

Case b: Student model also learn to mimic intermediate layers as well as the output. So the loss of the student is therefore the sum of all the intermediate losses and output loss. This was successfully applied in Patient Knowledge Distillation for BERT Model Compression

The image shows the model architecture of Patient Knowledge Distillation approach to BERT model compression. In the PKD-Skip architecture, the student network learns the teacher’s outputs in every 2 layers while the PKDLast represents where the student learns the teacher’s outputs from the last 6 layers.

A major advantage of the teacher-student setup is that it provides flexibility over size, as there is no restriction on size of teacher and student. A consequence of this smaller model is its fast inference time, with similar performance as the teacher. One thing to put in mind is that a pretrained teacher model is required in this setup and the student network inherits the biases of the teacher model.

Knowledge distillation has been successfully applied to production models such as the HuggingFace DistilBERT with a smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter BERT model. It has also been applied in Generative Adversarial Networks, KDGAN for student training. In another area of application, knowledge distillation can be used to train a surrogate model without having knowledge of original model internals or even its training data. The paper titled “Practical Black-Box Attacks against Machine Learning” highlights the fact that this can aid adversarial attack of a machine learning model as the surrogate model just has to learn to mimic the decision boundaries of the original model. -

Pruning

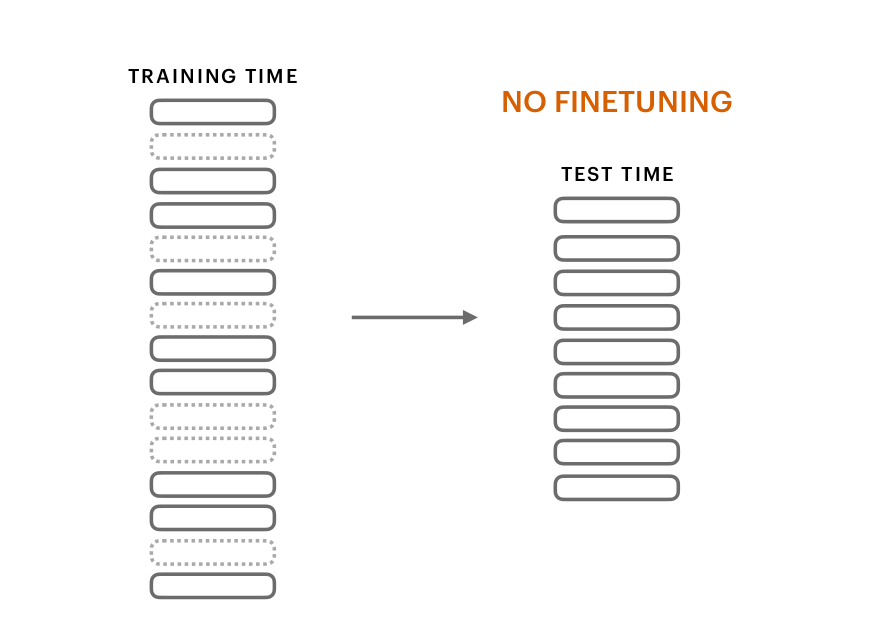

Pruning involves training a large network at training time, but then eliminating some parts of the network at inference time. This might include heuristics such as dropping convolution layers, dropping attention layers, or convolution filters, removing portion of weights etc. at inference time. The method above usually require some for of retraining or finetuning. Can we have a method that does not necessarily need retraining at inference time?

A recent work by Angela Fan on LayerDrop showed promising results. The layer drop is so simple that it is surprising that it works at all.

How LayerDrop works

LayerDrop is implemented by randomly dropping layers during training using a drop rate. Possible drop rates are 10%, 20%, 25%. Its implementation is similar to dropout but does not even require that weights are upscaled after dropping layers.

Also, LayerDrop increases training speed as we do not perform forward propagation on the entire number of layers, ensuring that the model is robust to perturbations and regularized.

At inference time, you can prune to any depth of your choice without affecting performance. This means that you can adopt any pruning strategy e.g. prune all odd layers, or prune all even layers, or prune every 3 layers. Pruning strategy that may not work well are aggressive pruning e.g pruning all the early layers or pruning all the late layers or pruning more than 50% of the model.

LayerDrop has not seen wide success in computer vision as it has in NLP though, but more research can be done in this area. - Weight Sharing

The idea of weight sharing is that different layers can reuse weights. This just requires that some or all sub-networks share the same weights. A major drawback of weight sharing is that the amount of transformations that can be learned is reduced, casing a decrease in performance. In practice, the model capacity is usually increased to cater for this. The ALBERT model utilizes this idea of tying chunks of layers to the same weights. As quoted from the blog post;“Another critical design decision for ALBERT stems from a different observation that examines redundancy. Transformer-based neural network architectures (such as BERT, XLNet, and RoBERTa) rely on independent layers stacked on top of each other. However, we observed that the network often learned to perform similar operations at various layers, using different parameters of the network. This possible redundancy is eliminated in ALBERT by parameter-sharing across the layers, i.e., the same layer is applied on top of each other. This approach slightly diminishes the accuracy, but the more compact size is well worth the tradeoff.”

-

Quantization

Quantization refers to techniques for performing computations and storing tensors at lower bitwidths than floating point precision. This process compresses the model size after training and a go-to approach for model compression, especially for on-device AI applications.

In quantization, the goal is to efficiently store the weight floating point numbers using other number types such as int8, int4 or even bits(1 and 0). This is usually more memory efficient. The popular deep learning libraries provide quantization methods out of the box and have tutorials on how to perform quantization. See Tensorflow and PyTorch libraries for their apis.

Quantization can drastically reduce model size by up to 80% and can easily be combined with other existing techniques for even lower model sizes. The quantization method and compression size has to be considered because drastic compression can reduce model performance and accuracy. - More Efficient Architectures

As at this time, we have been exploring methods that involve starting with a bigger model, then compressing it. Can we do better by consciously building architectures made out of the goal for efficiency?

For example, this paper titled “Pay Less Attention with Lightweight and Dynamic Convolutions” replaces some multihead attention weights in transformers with convolution layers. Some other propositions might include eliminating some bottlenecks in our current networks for faster computation, if it will not affect performance. Also, application specific models can be built for better efficiency.

Some other considerations for efficient networks which were not discussed in this article are; models for specialized hardwares and specialized memory block sizes. These are also great considerations for efficiency and important for hardware manufacturers who have their chips optimized for computation in this regard.

Conclusion

In summary, we discussed what it means for models to be efficient, looked closely at neural networks to garner intuition about their behavior, described current methods for making models more efficient and took a step forward to provide a glimpse of building more efficient architectures from the get-go.